Names don’t get much more evocative than Samarkand. The name conjures up the very essence of the Silk Road – bustling bazaars, winding back streets, dusty ramparts looking out over the desert, weary travelers discussing the price of carpets in the streets. The Silk Road is a region of extraordinary history, with ravening hordes descending from every direction every few hundred years, carving up vast territories into huge empires before falling, either to the next onslaught or to internal decay. Lucy and I have been wandering hand in hand through the streets of Khiva and Bukhara absorbing the old world atmosphere (and eating kebabs – dozens of them) and dreaming of Samarkand, Kashgar and all the places to come in this stage of our trip.

But yet, I hear the question on everyone’s lips. The burning issue of such import, high above all other burning issues: did you manage to go running?

Well no. It turns out that beautiful pre-medieval towns are utterly rubbish for jogging. They are all far too small and far too wiggly – you would end up going round and round in loopy circles getting more and more lost. And people would stare. However, in the epic historical thread of empires in the region, the most recent to fall was, of course, the Russian empire. And Russian town planners just loved straight lines.

It’s easy for those of us who have spent most of our adult life in a post Soviet world to forget about the influence of the Russians in the ‘Stans. Such influence was, of course, utterly transformative. The old towns of Khiva and Bukhara may have escaped without too much adaptation, but that is to ignore the wider Russian impact. They dug some of the longest canals in the world to irrigate the region – the fields that you drive through for hours between cities were all historically rolling desert, with just a few oases supporting the few large towns. The Russians introduced heavy industry in ideologically acceptable places, now largely rusting in picturesque piles. They introduced cotton and in doing so generated vast revenues while encouraging some pretty epic environmental destruction. And they utterly transformed the shape of the cities: wide boulevards replaced winding streets; soviet-style concrete apartment buildings line said streets; while at ground level you find soviet-style shops, which somehow manage to look drab even with a post-independence abundance of goods in them. Concrete and grass parks surround sporadically working fountains, even if the socialist realist statues of revolutionary heroes are now largely gone, or replaced with less political historical figures.

As a “centre” of the Silk Road with large and impressive monuments (and thereby fitting nicely with a centralized ideology) Samarkand benefited from some intensive and expensive restoration work in the 1970s. As a result, the monuments are all deeply impressive, and are placed within an appropriately Soviet hub and spoke road system, complete with pedestrian areas lined with glass fronted shops and restaurants. And it was through these pedestrian areas and along these boulevards that I ran, appropriately awestruck at the sights but wondering slightly where all the charm had gone.

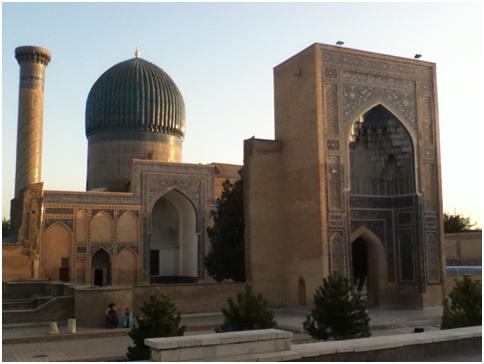

Start and finish point by our guest house – the mausoleum of Timur the Great (or Tamurlane, as he is sometimes called in the West)