We arrived at the little port of Pagwe, on the banks of the Sepik, after a bouncy 4 hour ride in a minibus, broken only by a short stop at a local market for us to buy some fresh produce. At the time, we couldn’t quite work out why we were being encouraged with such enthusiasm to treat ourselves to a (delicious, by the way) young coconut, though this later became clear (see “Tuna’n’Noodles” post for further detail). Waiting for us at the dock were our dugout canoe – all 20 foot of it, hand carved some 50 or more years ago from an exceptionally hard wood which grows locally – plus our crew for the next few days – George, Chris and our guide, Josh. Deck chairs having been ceremonially placed in the canoe for us (the crew sat in the bottom of the canoe, but obviously us tourists are special) and our luggage and food supplies loaded, we were off!

The basic program for our trip was: day one – stop at some local villages on the main river to check out the spirit houses (more of which later); day two – head down to Blackwater Lakes, a stunning area upstream from the river and at comparatively high altitude where the style of the villages – lots of stilts – is particularly attractive, as is the mountainous background; day three – head to Chambry Lakes, another scenic area where the fish are so plentiful that as the lakes dry up in summer, it’s just not physically possible to catch them all and the area becomes quite smelly; day four – return to Pagwe to connect back to Wewak early the next morning.

So basically, 4 days spent mainly sitting in a remarkable old dugout canoe, watching river life gliding by. Amazing scenery. Hundreds of water birds (ibises, fish eagles). Scores of local people out fishing in their dugouts, all of whom wave at you as you go past – we felt like the Queen. Then we’d pull into some village somewhere and see what there was to see – generally, a spirit house or men’s house containing the traditional village cultural things (and some carvings to buy – yeah!), maybe a health care centre or a waterfall. Return to the canoe and pootle on a bit before coming to a rest in a local village where we’d stay the night. At night, mainly just some relaxing time with the locals (though we did go crocodile hunting the first night – more exciting than it sounds, the largest we saw was about 18 inches!!). Unbelievably relaxing, and yet the trip, and in particular the way of life of the local people, gave us a huge amount to think about – we were certainly never bored.

The comedy part of our trip came from the organizational front – or rather lack of it.

We got our first hint of this as we rocked up to the village guesthouse on day one – only to be chased out again thirty seconds later. The guesthouse had been badly overbooked (all guests of Seby…oops), with 21 people fighting over about 12 rooms / bedding piles. Fortunately, we were rescued by Sara, Seby’s sister in law, who carted us off to her house and put us up for the night with only the tiniest of avaricious glances at our food supply box to provide an inkling of an explanation as to this unlooked for generosity. Part of the deal we struck was that any food we didn’t eat would go to her (as would some of the other more random supplies we carried – 2 bottles of curry powder, a couple of boxes of Ziploc bags … anyone would think the supplies had been provided specifically to address certain village requirements rather than to feed us for 3 days). Actually, whilst it got a bit grating, her continual exclamations as to how lucky we were felt pretty accurate as we chatted around the fire for a couple of hours, listening to the sounds of our fellow tourists haggling over the last sleeping mat.

Our next hint came via a delegation, led by our guide, Josh, wanting to know what we planned to do over the next few days. The itinerary, so carefully planned with Seby, hadn’t been communicated to him so he had no clue as to what he should be doing.

This, as it turned out, was exacerbated rather by the fact that Josh had never guided before. He told us this on day 2 – James asked how long he’d guided before, to which the merry response was “But I’m not a guide!!” (sub voce: what the hell made you think that??). 50 miles from the nearest cell phone signal, we gulped, smiled and accepted it.

The break though came later that day – a clear understanding between us and Josh (a) that we knew that he knew that we knew that Seby had totally failed to make any kind of plans whatsoever for us and that as a result, we and Josh were sort of relying on being helped out by random friends and family of Josh and (b) that we didn’t mind a bit – we were having a fantastic time, a complete adventure, and Josh was an unbelievably good guide – he is the main tradesman used by his village when they run out of sago and have to trade with other more sago-rich villages downstream, so he knows the river, and most of the people on it, backwards. After which, we all rubbed along together just fine and Josh noticeably relaxed – to the extent that he was then perfectly happy the next day to act as our supplier for banana homebrew, despite the severe consequences of being found out in that activity by Sara, a committed Seventh Day Adventist (and also someone who was clearly keen that we spend most of our time sleeping and thereby consuming only a minimal amount of our food supply!).

We had a wonderful time on the river. The mild chaos was oddly part of the charm – it never interfered with our pleasure and I think in most instances enhanced it. Staying with Sara gave us a real perspective on modern life in the Sepik, that I don’t think we would otherwise have really understood. And Josh, once he’d realized we weren’t going to explode on him, was an entertaining and informative guide to a part of the world he clearly loved.

Or maybe my hindsight is just coloured by realizing just how fortunate we really were – another group of Seby’s who we met in Wewak had spent 3 days eating peanut butter and crackers after Seby forgot to restock the boat with food.

Compared to which, our trip was LUXURY!

-

-

Life on the canoe….yep, it’s as tough as it looks

-

-

Pulling into our first village. Sculpture shopping ahoy! Oh and some cultural stuff

-

-

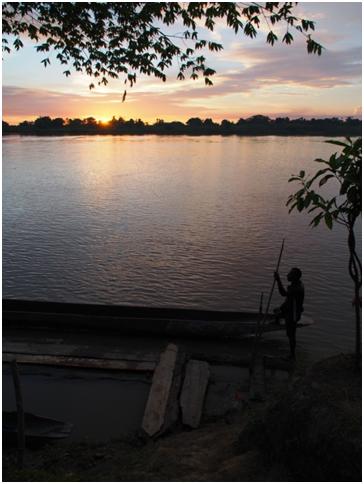

Sunset from the canoe. Hard to find a more tranquil setting

-

-

Our home for 2 nights on the river, plus Cats the amazing rat catching cat

-

-

Our bed. Yep, just as comfy as it looks……am I too old for this?

-

-

Day 2 and a tasty and nutritious post breakfast snack of (not very sweet) sugar cane

-

-

Winding our way through floating islands. Yes we did get stuck, though only once and it wasn’t my fault

-

-

Amazing views in Blackwater Lakes (totally worth getting stuck for!)

-

-

Crowding’s terrible on the river….all those eagles’n’ibises…..